Coloring Outside the Lines

Have you ever watched a child color? The look of excruciating pain fills the determined little face – a vice grip on the crayon, head cocked, tongue firmly pressing against the inside of the cheek. Sheer exhaustion before they put a lick of pigment on the paper.

It’s hard to remember the first time I sat down with a coloring book in my lap and a slick, awkward crayon poised between my fingers. I can imagine my facial expressions, because, years later, my own budding artists served as a mirror to the past. The focus comes from an earnest effort to be accurate and to color within the prescribed borders. Think back to that brand new box with all the crayons in order: perfectly sharpened and lined up, standing at the ready, and a coloring book with intact binding and a ton of possibility, by its side.

I may not remember the specifics but I do recall that even as a beginning colorist, I could not accept any errant marks. Large, heavy “X” marks of frustration, big scribbles over perceived mistakes, pages ripped out, wads of paper on the floor. I shed an occasional tear for sure.

Now that I’m in my fifties, I actually want to color outside the lines.

Not all the way out to the edge of the paper, but far enough out to keep life interesting.

But what does this look like?

Do you mix plaids and stripes?

Do you garden naked just because you live in the country?

How do you do it ? How do you pull it off?

There’s some tribal something that still holds me back, just a little.

How about actually creating the lines as you go?

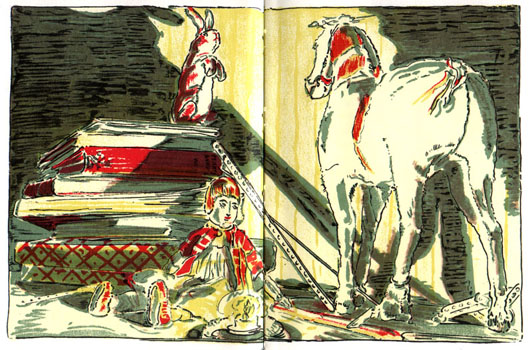

Remember HAROLD and the PURPLE CRAYON, by Crockett Johnson? Harold begins a creative adventure, putting his trusty purple crayon to work on a blank canvas. If he wants something to exist, he draws it. Even at four years old, he’s figured out that there is a certain order to his world. His true character develops through wiggling out of tight spots and overcoming obstacles, which are encountered along with the way.

“But this is no hare-brained, impulsive flight of fantasy. Cherubic, round-headed Harold conducts his adventure with the utmost prudence, letting his imagination run free, but keeping his wits about him all the while. He takes the necessary purple-crayon precautions: drawing landmarks to ensure he won’t get lost; sketching a boat when he finds himself in deep water; and creating a purple pie picnic when he feels the first pangs of hunger.” Goodreads

Take a yoga breath, relax and loosen the grip on your crayon. Trust yourself and create a masterpiece.

The Skin Horse Tells His Story

The Skin Horse Tells His Story